This piece is the fifth installment of a biweekly series written by David A. Foster (Center bias), based on his new book, Moderates of the World, Unite! Read the first post in the series.

When radioactive material is brought together in high concentrations in a nuclear reactor, control rods must be inserted to regulate the heat.

A new age was inaugurated when millions of genetically tribal, half-informed citizens were brought into the seething cauldron of social media. Suddenly, motivated reasoning met high-proximity social networks. Chris Bail has described the status competition in social media, inducing extreme partisans to do most of the posting, driving moderates out, and distorting the image of the other side.

Unfortunately, no control rods have yet been inserted into social media, and the heat has generated a crippling national political polarization.

Of course, social media companies are interested in profits, not control rods. Profits come from engagement, not from protecting the public interest.

For their own interests, social media companies do have to respond to criticism from politicians, advertisers, and the media. Token efforts are made. But the mechanism is crude censorship: blocking neo-Nazis and conspiracists, blocking smut, and blocking disinformation. None of this gets at the deepest issue: that partisan talking points are passing for legitimate thought, and that most online users really are unaware that it’s happening.

If they became aware of it, they would not reward it so much, and neither, consequently, would the platform algorithms. The status accorded to propagandists’ content would diminish. Divisive rhetoric, straw men, slogans, false narratives, insinuations, and fallacious premises can’t realistically be blocked; however, less of it might get produced.

Certainly these companies will never hire new moderators to do the job of finding and flagging uncivil and (let’s term it) “low integrity” posts. And it is almost as inconceivable that the companies might apply AI to automatically chastise or stigmatize posts that are not constructive. Would that ever happen? Antagonizing their most active users? Affixing bot-generated critiques to every excessively-tribal post? No, their users wouldn’t stand for it. It would be a bad business decision.

The hackneyed proposal is that our citizens need to have more critical thinking skills so they’ll understand what is going on online. Sure, but... will a few lessons in school about logical fallacies ever do the trick? I don’t think so. Based on what I know about cognitive learning theory, I believe the education needs to occur in context.

A Solution: Education In Context

What’s needed is an independent organization employing an army of specially-trained moderators who evaluate posts and attach information to them wherever issues are discovered. Only a small percentage of “bad” posts will ever get this review, but that’s absolutely fine. In fact (I’ll argue), even with a small percentage, it will change the entire psychology of online interaction for everyone on the platform.

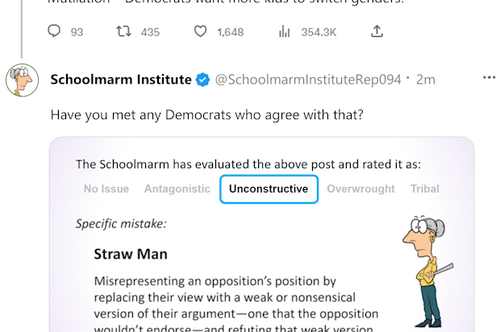

A post (or response) that’s evaluated and found to have an issue gets an icon affixed to it, or a prominent, branded response.

Any user who then sees the response and/or clicks on the icon sees a full explanation of the issue. For example:

Sample reply to a post that has divisive rhetoric.

We can refer to our moderators as “Civility Moderators” or “Quality Moderators” to distinguish them from the moderators employed by the social media company itself. To achieve reliability and scalability, the issue descriptions aren’t written by the Quality Moderators themselves, but rather are pre-written by the Schoolmarm Institute and supplemented with just a little contextual customization.

Linking into the educational content base.

This organization would have to be stringently and constitutionally non-partisan. The simplest solution would be to guarantee that an equal number of right-biased and left-biased critiques are posted each day. An ongoing record of all critiques and statistics would be made publicly available.

Quality Moderators would not randomly search for candidate posts, which would be hugely inefficient. Rather, AI algorithms would expertly look for the most promising “bad” posts and queue them up for the Moderators to review.

Highly simplified mockup of basic elements in the Quality Moderator’s cockpit.

The algorithm could also make initial assessments about the poster’s partisan leaning and the issue category. Again, Moderators are never fact-checking or making judgments about misinformation. Rather, here is a sample taxonomy of issues they would flag, with a selected handful of subtypes listed for each:

Antagonistic: Ad Hominem; Belittling; Inflammatory Words; Smearing

Unconstructive: Cherry-Picking; Straw Man; False Dilemma; Slippery Slope; Whataboutism; Worst-Case Filtering; Gish Gallop

Overwrought: Catastrophizing; Hyperbole; Sanctimony

Tribal: Accuse Heresy; Narrative; Out-Group Homogeneity; Subordinating Rationality

A fuller list can be seen on this prototype site.

A critique typically will have the most intense effect on the user whose post is critiqued. The user is, of course, free to post a rebuttal or defense and will learn in that process. Because the critique is coming from a real human being rather than an AI bot, the user’s reaction would typically be less scornful, and the critique will generate more curiosity.

Each critique is also seen by many other browsing users. As previously indicated, it will only be possible to post critiques on a small percentage of all “bad” posts on the platform. However, if enough critiques appear over time such that most users at least occasionally see such posts, it will affect the psychology. They will tend to be a little more careful with their own posting, and they will think more about quality issues whenever they see problematic posts by others (whether marked or unmarked). General awareness about fallacious and rhetorical excess goes up, and more people will tend to look down on instances of it.

Social Media Companies’ Cooperation

It might be asked whether this kind of approach could be achieved “for free” by crowdsourcing. The X platform has touted an approach to fact-checking and misinformation that it calls Community Notes. Other platforms may also try to implement a similar approach because of the PR value and because there is essentially no operational cost. Unfortunately, the approach has mostly failed. Meanwhile, when it comes to rhetorical issues (rather than fact-checking), the crowdsourcing approach would likely be even less successful. Users would not trust the impartiality of untrained critics, and there would not be professional accountability like that enforced in the Schoolmarm Institute.

So the question looms: what kind of cooperation by social media companies would be needed, and how could it be obtained? This is a complex issue that I discuss more in my book, but here are a few key points.

It might be possible to operate the Schoolmarm Institute without any cooperation at all from a social media company, as long as the company permitted it to create accounts and the critique posts were not blocked or demoted. However, it would be difficult to achieve a scalable impact unless the company also allowed access to its platform’s public API so that current posts could be efficiently searched.

Deeper platform integrations would also be possible and beneficial, for example, providing specialized icons and pop-ups within the platform’s own user interface. (With all the quality-moderation labor, of course, supplied by the Schoolmarm Institute.)

Some social media companies might see cooperation as a useful PR opportunity because it would appeal to politicians, the public, and (not least) advertisers. Others might only respond to public pressure or arm-twisting.

Philip Napoli has written eloquently about social media and the public interest. He advocates the development of an industry association—similar to what we’ve seen in the past with the media industry—that develops standards and imposes some measure of self-regulation.

However, given the negative effects that such an initiative could have on profitability, and given the power of social media corporations, one may reasonably doubt that it will occur in the foreseeable future. Cooperation should thus be specified and compelled by Congressional action.

Summary

The Schoolmarm Institute could thus insert into social media the “control rods” that are so desperately needed by our democracy. The temperature of national discourse could start to be controlled.

As with the proposal in the previous article in this series, this approach continues the theme of shaping the speech environment. Never censoring any individual speech.

Read the rest of the series: