Financial Times

The Financial Times has a media bias rating of Center. The Times is an international newspaper that focuses on business and economic reporting.

We’ve been told for years that rich countries have had enough of immigrants, so it’s confusing to hear what several governments are now saying. The new German coalition has drawn up measures to import more workers. Japan has been abandoning ethnic homogeneity, and is considering letting some blue-collar immigrants stay indefinitely. “People with different backgrounds make Tokyo only more attractive,” said Yuriko Koike, the city’s governor.

Elsewhere, “California leads the nation with pro-immigrant policies,” claimed the government of the most populous US state as it officially binned the word “alien”. In Canada, where new permanent residents hit a high last October, the immigration minister boasted about exceeding targets, and talked of raising numbers further. And only 45 per cent of Britons want to cut immigration, according to pollsters Ipsos Mori. That’s the lowest figure since the question was first asked in the 1970s, reports think-tank British Future.

It turns out that majorities can sometimes accept higher immigration. In what circumstances? And how can we globalists encourage acceptance?

A flood of research has clarified attitudes to immigration, reports the ODI think-tank. The first finding, from which all discussion should proceed: “Around the world, few want more immigration.” For instance, of 22,000 citizens in 20 democracies interviewed by YouGov and Global Progress last year, 53 per cent said too many immigrants were coming to their country, while only 8 per cent wanted more.

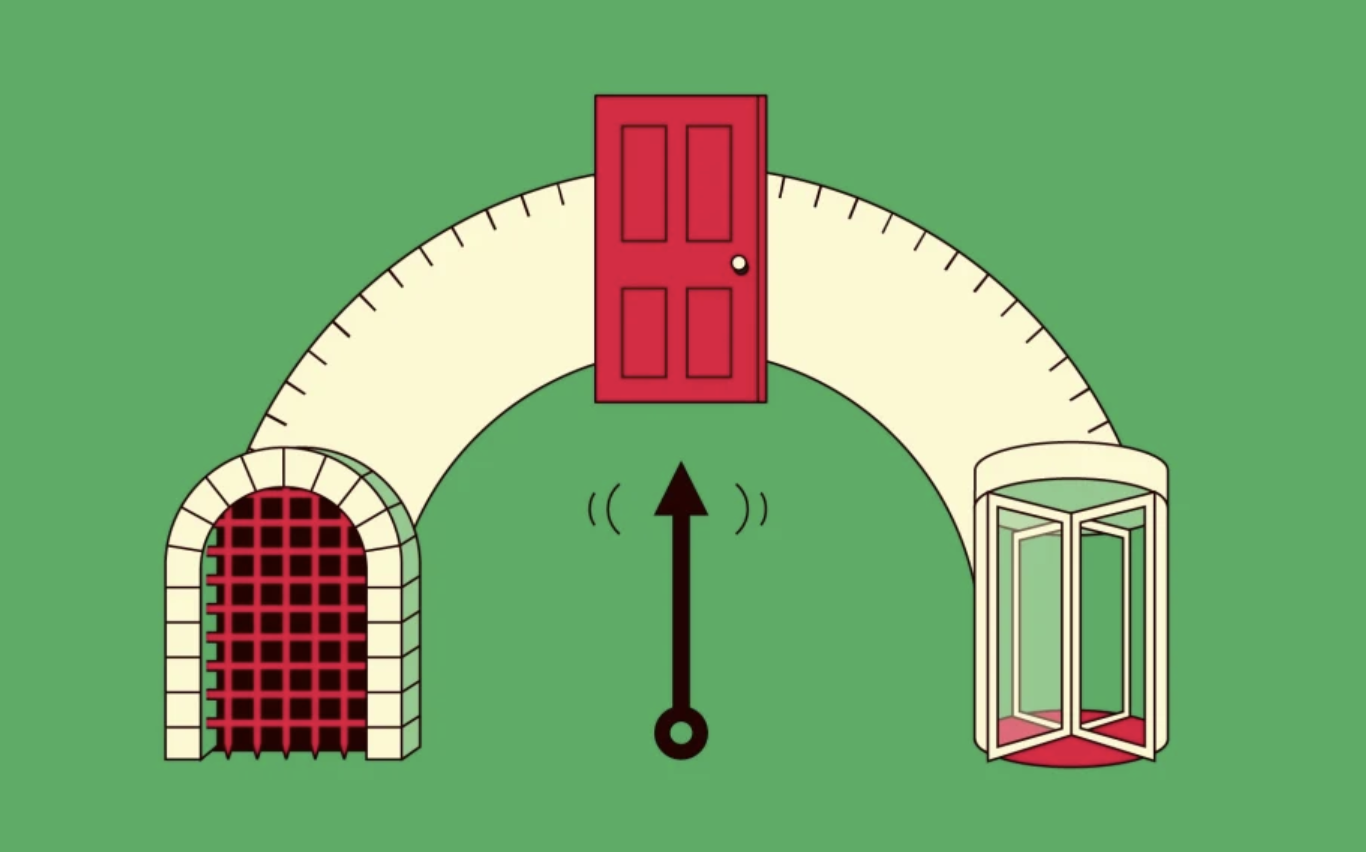

Yet it’s misleading to portray the immigration debate as binary: the nativist “real people” versus a handful of deluded wokesters. Rather, says ODI, the “shape of opinion across different countries is notably similar”: “the largest section of the public” clusters in a “conflicted” or “anxious” middle, which is ambivalent about immigration and is “relatively open to effective persuasion”. So the debate hinges on persuading the middle. Only in a few places, such as blue US states, can that be done by waging culture war: if Donald Trump is against immigration, then the Democratic majority will be for it. But in most countries, you win the middle by turning down the emotional volume and assuaging people’s worries.