Bloomberg

Media Bias by Omission: Bloomberg Doesn't Investigate Democratic Presidential Candidates

As of Nov. 2019, Bloomberg admits that it engages in bias by omission with a Lean Left bent. Mike Bloomberg, New York City mayor and founder of the financial software company that owns Bloomberg, officially entered the 2020 Democratic presidential race in Nov. 2019. According to a memo sent to editorial and research staff obtained by CNBC and verified by a Bloomberg spokesperson, Bloomberg News announced it would refrain from investigating Mayor Bloomberg and his Democratic rivals.

“We will continue our tradition of not investigating Mike (and his family and foundation ) and we will extend the same policy to his rivals in the Democratic primaries. We cannot treat Mike’s democratic competitors differently from him,” Editor-in-Chief John Micklethwait said in the memo.

In Dec. 2019, President Donald Trump's campaign announced it would stop credentialing Bloomberg News reporters for rallies and other events until the outlet resumed investigating Democratic candidates.

Mike Bloomberg is founder and 89% shareholder in Bloomberg LP, the financial software company that owns Bloomberg News.

Confession: This column was originally going to be a downer. Perhaps it would have had a headline that said something like, “Is this the last Black History Month?”

It makes sense to be pessimistic about the fate of this February tradition, given the political climate around issues of diversity and the battle over how race and history are taught in schools. Nikki Haley, who wants to be president, erased slavery from the Civil War, then she suggested America was never racist and then seemed to argue that America’s founders really envisioned a nation of equals, but getting to that point was akin to fixing a clerical error.

Across the country, at colleges and corporations, diversity and inclusion initiatives are being targeted, as are Black academics. Black books are among the most banned. The post-George Floyd “racial reckoning” faced a huge backlash and never quite materialized for any sustained period of time. Sure, there are now bandages that match the skin of Black people (imagine that!) and Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben are no more, but is that all?

But, as I got my 3-year-old daughter off to school and caught a glimpse of her bright turquoise Rosa Parks sweatshirt, my thoughts began to wander. I thought about how different my daughter’s experiences have been and will continue to be from my own. I thought about how hard it was for my mom, an educator, to find Black children’s books when I was a kid. While our bookshelves were filled with books about African-American history because my dad was a historian of American slavery, books featuring little Black girls and boys doing little kid things were in short supply. At times, my mom was so desperate for us to see ourselves in books, she would use a brown crayon to make the White characters look more like we did. (This was not convincing even to a kid). While my mother had dreams of having a Black doll collection, store shelves simply didn’t carry them so we rarely had them. (She ended up making me a Black Cabbage Patch Doll. Also, not very convincing).

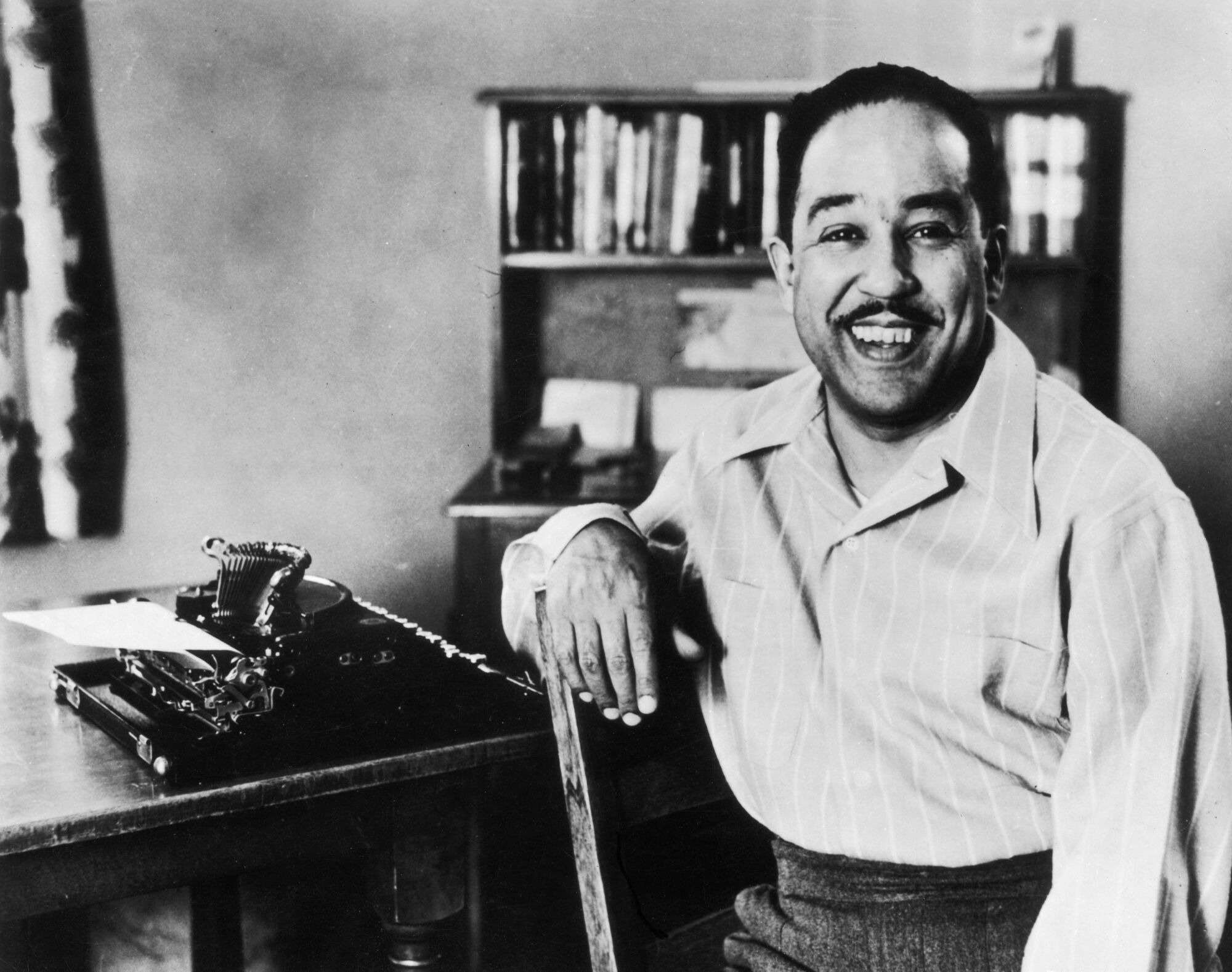

As for school, there was minimal focus on Black history. I was assigned one book by a Black author (Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison) in my 12 years of primary education at predominately Black public schools in my small Southern hometown. That was my senior year, for AP English. We also watched the movie Glory that year. I vaguely remember a trip to the statehouse where bullet holes from the Civil War were pointed out. But I brought my blackness to school. For my third-grade declamation contest, I chose to recite Langston Hughes’ I, Too while other kids chose Shel Silverstein. Roots was a Christmas movie in my house. And by high school, I was devouring books by Black authors like Margaret Walker and scolded for reading them in class.